One of the hidden treasures of old Calcutta is the Maghen David synagogue along with the remains of the Neveh Shalom Synagogue immediately next door. It is located just north of the area known as Old China Bazaar, which is no longer a China bazaar, and similarly, the area that once housed the Jewish population of the city no longer boasts any Jews. Once, it is reported, there was a sizeable Jewish presence in the city - many thousands - and the remaining synagogue is evidence of the fact. But, just as the Chinese population has dwindled to nothing, so too the Jews. Today, the present writer was informed, there are no more than about twenty Jews resident in Calcutta, too few to constitute an active congregation of observant worshippers. Accordingly, the synagogue lays idle, although it is fully preserved. It is hidden behind rows of street vendors and the mad bustle of the modern city. It is difficult to locate, and the entry door even more so. The writer tried several entry ways, all of them barred up or barricaded, before finding an iron gateway that opened into the yard of the synagogue. It was padlocked, but a young Hindoo motioned to come forward and wait and in due course a Mohametan fellow emerged from inside with the keys.

It is the irony of the Maghen David synagogue that, these days, there are so few Jews in Calcutta that the building has to be minded by a Muselman. He was happy to open up the building, turn on the lights and give a tour, explaining a few points of history in his broken English. There is an old Jewish lady of Calcutta, he said, who has been resident since before Partition, and she visits the synagogue every sabbath, largely to check upon it and to ensure the building is still intact. There are not enough Jews to form a quorum, though. Two copies of the Torah lay unused behind curtains. In every respect, though, the building is in magnificent condition - the synagogue with no Jews. It was built in 1884 at the sole expense of Mr. Elias David Joseph Ezra, Esquire, on the grounds of the older adjoining synagogue, the Neveh Shalom, as an inscription at the entry way explains.

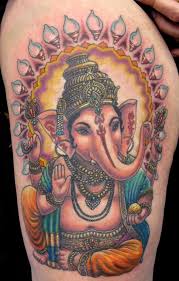

There is a large sign at the entry way explaining that photographs are strictly forbidden, but the young Muslim who allowed the present writer into the building insisted. "You take picture," he said. "May I?" "Yes, yes." He received twenty rupees for his trouble. Some of the resulting snap shots are below. (Click on a picture for a larger view.)