There is enough distance now from the watershed year of 1989 to revisit the life and work of the great English engraver and master craftsman Eric Gill. Up until that year Mr Gill had been a favourite of many, including the Traditionalists with whom the present author was at that time associated. Gill was touted as an outstanding modern representative of the traditional arts and crafts and no less an authority than A. K. Coomaraswamy wrote in his favour with great enthusiasm. But then a tell-all biography that drew upon his previously unreleased diaries was published and the rather deviant sexual life of the artist became public knowledge. It was revealed that throughout much of his adult life he had been happy to frolic not only with his wife and innumerable lovers but with his sister, his daughters and his dog as well! He recorded these exploits in detail in his journals and appears to have had no qualms or conscience about them at all. His reputation suffered.

He is, for this reason, a strange case. His extraordinary sexual life was in glaring contrast to his devout Catholicism and his undoubtedly sincere spiritual demeanour. Indeed, he seems to have been perfectly able to combine his erotic experimentalism with an otherwise monkish life and a deep dedication to the traditional arts. Those that knew him praised him as "the married monk." He founded the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, a guild for Catholic craftsmen informed by a Dominican monastic spirituality (see below). He was dedicated to a revival of Catholic aesthetics and to pioneering a new spirit of Christian art against the ugliness of modern mechanisation.

At the same time, though, as one of his daughters would later relate, he had an endless fascination for the erotic and in no way felt this to be at odds with his spiritual vocation. He is thus an enigmatic figure, or seems so to us, being a peculiar meeting of convention and deviance, high purpose and errant appetites. It is unfortunate, because he is far more interesting than the salacious sex life that has overshadowed him: he is an artist of great importance and entirely deserved the reputation he enjoyed prior to the 1989 revelations. He single-handedly led a revival of a traditional artistic sensibility and style appropriate to the modern era and the modern predicament. There are few things as decadent as sculpture in the modern era: Eric Gill led a one-man restoration of the art. Beyond question, he is one of the most significant religious artists of the modern era.

Yet we dwell now upon his erotic misdeeds and find him either fascinating or villainous, or both, and cannot refrain from viewing his work through a far more erotic focus than before. It rarely occurs to us in this that, whatever the facts about Mr Gill's private life, we of the XXIth century, though we bask in our own estimations of the degree to which we are "liberated" from the strictures of the past, are extraordinarily prudish and will send public figures to purgatory for the slightest sexual indiscretion. Gill was guilty of more than indiscretions, but we need to ask whether we are really in a position to fully understand such an artist. Our own erotic culture is, in fact, both narrow and shallow. In particular, popular morality has no accommodation for collaborations of sex and the sacred, whereas traditional cultures invariably do.

For Gill, in himself and also in his work, as we see it now, was absorbed by two things, sex and the sacred, and in his own mind he sought to reconcile them and, moreover, he did this through Catholicism. This is reported by those who knew him well. They relate that his conversion to Catholicism was in order to reconcile the sexual and the spiritual dimensions of his life. True, this does not seem to have included observing Catholic moral codes, but all the same Eric Gill found a unified vision of the erotic and the sacred in the Catholic faith. How? Are we really in a position to understand it? We live in times when feminist critics just yell "Rapist!" when Mr Gill's name is mentioned. They want him stricken from history. We live in times of on-going moral outrage. In politically intense times such as these we are not in much mood to try to understand the contradictions of Mr Gill's inner quest for meaning.

The kiss of Judas

Catholicism, all the same, is - when compared with Protestant forms of Christianity - a sensual, physical and visceral spiritual temperament. Protestantism is, by nature, much more cerebral and abstracted. It is a faith of ideas. Catholicism is a faith of physical encounter. And this is what Mr Gill wanted. He needed a spirituality that was deeply physical, even sensual. Protestants rarely appreciate this about Catholicism: that it offers a deeply sensual spiritual encounter. There is the deep sensuality of the Eucharist, the visceral literalism of the Real Presence. There is the deep empathy for the suffering on the Cross, for the wounds of Christ, the passion of Christ. There is the cult of relics - bones and other remnants pillaged from the corpse of saints. Works are physical acts. Devotion takes a physical form. This was entirely in accord with Gill's character. He was a sculptor by trade and temperament. He was a man of touch. Tangibility was a spiritual fact for him. He worshipped with his hands. He adopted the motto: "Man is composed of matter and spirit, both real and both good.” He found this doctrine realised in his Catholicism.

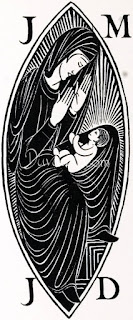

Madonna and Child with Angel

Much of the time in Catholicism, though, this sensuality manifests in forms that are sadomasochistic rather than in forms of erotic celebration. There is no gainsaying this fact. Catholic eroticism, where it enters Catholic piety and zeal, tends to the sadomasochistic. Nothing is as tangible as pain. Other converts to Catholicism have turned to the hair shirt, flagellation and extreme penances; for Gill - against all the moral teachings of the Church, it is true - it was a case of giving himself to unrestricted sexual curiosity.

A cynical view would be that this was entirely opportunistic, and convenient, the ruse of a lech, the narcissistic self-excusing rationale of a deviant sex criminal. But we have Mr Gill's art as a counter argument to this. There is nothing sordid or gratuitous in his work. Instead, it is - as we see very well now - a lifelong dialogue between the erotic and the sacred, congruent with and testifying to the sincerity of his life. His was a sincere attempt to live according to the motto: "Man is composed of matter and spirit, both real and both good" and his art, as much as his diaries, is a record of this motto realised.

His autobiography,(see here), begins with a chapter entitled 'Holes in Oblivion', being scattered recollections from his childhood. This is the oblivion, we might say, into which his reputation was cast after his sexual misdeeds were made public. He went from being a widely celebrated and saintly artist to suddenly being reviled and having his works removed from galleries and public places all across England. The Traditionalists with whom the present author was associated suddenly dropped him as their model of the modern spiritual craftsman. All the same, his work still speaks for itself - through holes in oblivion, as it were - and is a beautiful, if now problematic, record of Mr Gill's spiritual quest. This writer, at least, is still prepared to hold his work in high esteem and to try - putting aside all moral squeamishness - to understand it as a deep and sincere encounter of sex and the sacred such as has rarely occured in Catholic piety.

A cynical view would be that this was entirely opportunistic, and convenient, the ruse of a lech, the narcissistic self-excusing rationale of a deviant sex criminal. But we have Mr Gill's art as a counter argument to this. There is nothing sordid or gratuitous in his work. Instead, it is - as we see very well now - a lifelong dialogue between the erotic and the sacred, congruent with and testifying to the sincerity of his life. His was a sincere attempt to live according to the motto: "Man is composed of matter and spirit, both real and both good" and his art, as much as his diaries, is a record of this motto realised.

His autobiography,(see here), begins with a chapter entitled 'Holes in Oblivion', being scattered recollections from his childhood. This is the oblivion, we might say, into which his reputation was cast after his sexual misdeeds were made public. He went from being a widely celebrated and saintly artist to suddenly being reviled and having his works removed from galleries and public places all across England. The Traditionalists with whom the present author was associated suddenly dropped him as their model of the modern spiritual craftsman. All the same, his work still speaks for itself - through holes in oblivion, as it were - and is a beautiful, if now problematic, record of Mr Gill's spiritual quest. This writer, at least, is still prepared to hold his work in high esteem and to try - putting aside all moral squeamishness - to understand it as a deep and sincere encounter of sex and the sacred such as has rarely occured in Catholic piety.

*

* *

* * *

This is one of the most explicit images whereby Mr Gill brings together his two obsessions, the sexual and the sacred. Called 'The Nuptials of God' it depicts Christ having sex on the cross. This is a defining image - the quintessential Eric Gill.

* * *

Mr Gill's sexuality was inseparable, it seems, from his artistic identity. Much is explained by his theory of art. He held the view - and regarded it as traditional and therefore historically normal - that the artist co-operates with (participates with) God in His creation. Creating is a divine act. The artist is a creator by extension from the Creator Himself. Mr Gill, that is, worshipped a deity in its demiurgic aspect which, in the Christian account, is God the Father. The feminists are right about him. His religion is essentially patriarchal. It celebrates the creative male god. This is to say, it is essentially phallic. His position is exemplified by a drawing labelled 'God Sending' (see above) which shows God send (acting through) a young ithyphallic male: the phallic male as an agent of God, the phallus as the divine instrument of creation, erotic energy as the divine creative impulse in the universe and in man. That is central to the entire theological outlook of Eric Gill.

* * *

GILLS SANS

Mr Gill was intent on renovating the entire landscape of modern industrial life. One of his greatest creations was the font type now known as Gill Sans. It is arguably his most enduring legacy. It has been one of the most popular and widely used fonts of the modern era. Shortly after its creation it was taken up by British Railways for their signs and publications, and somewhat later it was adopted as a standard font by Penguin Books.

As well as Gill Sans, Mr Gill crafted numerous other fonts especially for the purposes of religious works. His typesetting and illustrations for Bibles are rightly famous:

*

* *

* * *

The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic 1920-1989

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE GUILD

The Guild is a society of Catholic craftsmen who wish to make the Catholic Faith the rule, not only of their life but of their workmanship and to that end to live and work in association in order that mutual aid may strengthen individual effort.

Supporting themselves and their families by the practice of a craft, the members choose St. Joseph as their patron. Further, having found the Dominican Order their most explicit teachers, they also place the Guild under the patronage of St. Dominic.

The Guild holds;

That all work is ordained to God and should be Divine worship.

As human life is ordained to God so must human work be. We cannot serve God and Mammon but we can love God and our neighbour. The love of God means that work must be done according to an absolute standard of reasonableness; the love of our neighbour means that work must be done according to an absolute standard of serviceableness. Good quality is therefore twofold, work must be good in itself and good for use. (From ‘Actus Sequitur Esse’, The Game, Sept.,1921).

That the principle of individual human responsibility being a fundamental of Catholic doctrine and this principle involving the principle of ownership, workmen should own their own tools, their workshops and the product of their work.

The Guild therefore aims at:

Making the goodness of the thing to be made the immediate concern in work.

Undertaking and imposing only such work as involves responsibility for the thing to be made.

Making the good of the work and the freedom of the workman the test of its workshop methods, tools and appliances.

THE RULES.

Members shall be

Practising Catholics

Earning their living by creative manual work

Owners of their tools and of their work.

Admission to the Guild shall be by the unanimous consent of the members.

Applicants for membership who fulfil all conditions for admission shall be postulants for at least one year and shall be known as Qualified Postulants.

Applicants, such as apprentices, may be admitted to membership who do not yet fulfil the third condition for admission, but shall remain postulants until such time as they are able to fulfil it and shall be known as Unqualified Postulants.

The approval of the Guild must be obtained for the entrance of any apprentice or employee to a member's workshop and such apprentices or employees must be Catholics.

A Guildsman may not enter into workshop partnership with a non Guildsman.

The members shall elect annually a Prior who shall represent the Guild in all its affairs and superintend the work of such other officers as may be appointed. He shall generally take care that the Constitution be observed.

There shall be a meeting of the members at least once a month to decide whatever may be required. Postulants shall attend the Guild meetings but without a vote.

It shall be the Guild's duty to encourage understanding and practice of its principles among its members by arranging occasions for their discussion and exposition.

Guildsmen shall meet in the Chapel for prayer in common on such regular occasions as may be arranged.

There shall be a regular Guild subscription for the upkeep of the Chapel and other expenses.

The Guild owns its land and buildings under the name of the Spoil Bank Association Limited.

The property is intended for occupation by Guild members and for use for Guild purposes only.

The Guild shall administer its property through its officers and at its meetings, but the property accounts shall go through the books of the Spoil Bank Association only.

Membership of the Guild shall include membership of the Spoil Bank Association Limited.