Some time ago a friend of the author related the story of how she had chanced upon a notable garage artist in Florida. Strolling the streets and frequenting yard sales, she spotted an oil painting that was to her taste. She found it to be unusually powerful and accomplished – far better than the type of amateur paintings one usually finds amongst the knick-knacks and detritus of backyard jumble sales. This was much more than a crude and derivative landscape made in an Adult Education course. Making further inquiries, she found that the painting had indeed been done by a local artist, the Cuban-American Yeilem Barzaga Garcia Zuniga, who – quite authentically – painted in the family home’s garage, an unknown, untrained ‘hobby’ painter, painting for ‘fun’ and only selling work here and there for a few dollars.

Yet it was immediately apparent that this painter was particularly talented and may not be aware of it herself. It so happens, of course, that very talented people may labour away quietly in their homes unnoticed and unappreciated for decades or more, before they are ‘discovered’ and their talent recognized. This is not usually a theme pursued in these pages, but in this case the work in question is so arresting and the artist so thoroughly unknown that it is worth making an exception. In addition, Barzaga's work is in a modernist vein not usually explored here, but again there is every reason to make an exception. The paintings of Yeilem Barzaga Garcia Zuniga are outstanding. There is a dynamism and emotional clarity that is rare. It gives the present author great pleasure to be able to feature them here...

This is finally the great divide between modernity and tradition. A traditional order is essentially vocational. The great moving force in such a society is what we might call 'karma yoga' - salvation through work. It was fully understood that a man might be justified to God and Heaven just by being a blacksmith or a scribe or a doctor or a soldier. Work was thus a spiritual path. Vocation is the very cornerstone of Plato's Republic. There is a type of work to which we are born, and in which we find deep fulfillment. All of this understanding had to be deconstructed because it is essentially at odds with the industrial mode of production. It survives in our surnames - "Mister Smith", "Mr Cooper" - but otherwise it has been displaced such that people work dreary and pointless jobs and pursue their 'vocation', their real work, after hours in the garage. Our true work has been turned into a mere 'hobby'. The present author once met an elderly gentleman who wove the most exquisite weavings - superb. 'How long have you been weaving?" he was asked. He said five years. Then he related that he had always wanted to weave, ever since he was young, but he had driven buses all his working life. Only when he retired did he have the leisure to apply himself to his true work. This is the great cruelty of the industrial order and its greatest failing. On this point alone it is to be condemned as an abomination. It is only in the abundance of late industrialism that some people - a few - find "careers" for which they have real "aptitude" (although, even then, this is never deep enough to constitute a spiritual path in itself.) For every thousand young men who only feel life is a-right when they are playing guitar, only one or two will get to make a living doing it. The industrial order is essentially inhuman.

But there is art. This is why much of modern art takes the form it does. It is in the face of an inhuman industrial order that one is force, along with Oscar Wilde, to say "All art is utterly useless!" Only thus can the artist slip free of the industrial paradigm. Art, at least, remains a sphere in which it is possible to express a true vocation. We still find painters who are driven to paint, just as, once, blacksmiths were driven to hammer and forge. Distinctions between art and craft are irrelevant here. The issue is the inner urge to create through skill. It is the demiurgic urge, properly considered (while in the industrial order we see the diabolic Demiurge, the demon of mad replication.) Among artists we find people who are painters by vocation - long after oil painting had any meaningful place in the culture and large, and long, long after there was money to be made in it. The artist-by-vocation will paint anyway. It is their very oxygen. It is an intriguing psychology, in any case. The classical account of it is found in Plato, with the "idiot" Socrates practising his peculiar calling among the craftsmen of Athens. More commonly today, sensitive souls take shelter in their vocation and find a quiet corner of the world - say, a garage converted into a studio - where they can spend their spare hours. This is the age of the amateur, taking that word in its proper sense - an amateur = one who does what they do out of love (amor), one who loves, one who works for love.

But there is art. This is why much of modern art takes the form it does. It is in the face of an inhuman industrial order that one is force, along with Oscar Wilde, to say "All art is utterly useless!" Only thus can the artist slip free of the industrial paradigm. Art, at least, remains a sphere in which it is possible to express a true vocation. We still find painters who are driven to paint, just as, once, blacksmiths were driven to hammer and forge. Distinctions between art and craft are irrelevant here. The issue is the inner urge to create through skill. It is the demiurgic urge, properly considered (while in the industrial order we see the diabolic Demiurge, the demon of mad replication.) Among artists we find people who are painters by vocation - long after oil painting had any meaningful place in the culture and large, and long, long after there was money to be made in it. The artist-by-vocation will paint anyway. It is their very oxygen. It is an intriguing psychology, in any case. The classical account of it is found in Plato, with the "idiot" Socrates practising his peculiar calling among the craftsmen of Athens. More commonly today, sensitive souls take shelter in their vocation and find a quiet corner of the world - say, a garage converted into a studio - where they can spend their spare hours. This is the age of the amateur, taking that word in its proper sense - an amateur = one who does what they do out of love (amor), one who loves, one who works for love.

Entitled 'Loneliness Companion' this seems an especially significant work in a series called 'Windows for Closed Doors': this closed door and its three primary colours.

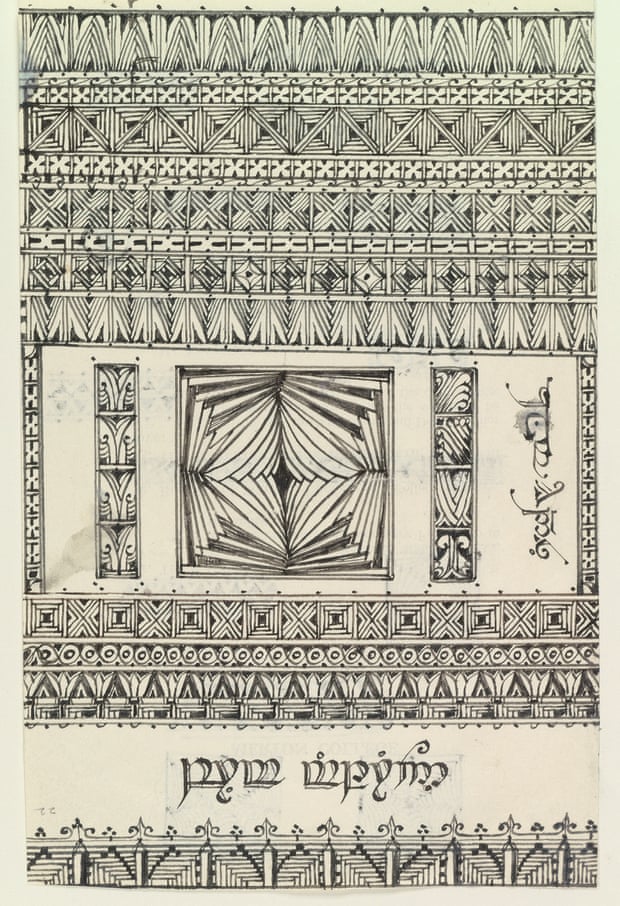

On her webpages Barazaga offers almost as many photographs of her studio working space as she does completed paintings. In many respects, these in situ photographs are artistic statements in themselves. In many respects, they are as interesting as - or even more interesting than - the finished paintings, as images. We can see the world of the artist: its vivid colours and its mysterious (ancient) faces. This is the world into which the artist disappears every chance she has. This is where she breathes. She has entitled a collection of her paintings "Windows for Closed Doors" signalling the intention to provide a purview into a private and inner world. But there is no element of voyeurism in this. These paintings are not part of the modern world's obsessive need to expose all mysteries to the light of day. The paintings are indeed mysterious. The mysteries are revealed and then left to be mysterious, not dispelled. In the best cases, the vehicle of mystery is colour. It would be wrong to say the colours are 'bold'. They are not trying to be. These are (usually) strong figures, but not 'bold'. The colour illuminates a necessarily inner world, and often makes no reference at all to external conventions.

Interestingly, though, many of the photographs she offers of her studio have been rendered into monochrome, stripped of colour. Colour is the soul of her paintings, yet the artist wants us to see her studio in black and white. Amongst other things this has the effect of making the space seem more industrial, much more a place of labour.