There is a charming story concerning the naming of the 1930s ocean liner the HMS Queen Mary. Constructed by the Cunard Line to run services across the Atlantic during the great age of ocean travel, it was first proposed that the ship be named the Queen Victoria. This was in keeping with the Line’s previous policy of having all of their fleet take female names ending in the suffix –ia. It was necessary, however, to seek royal permission for the use of Queen Victoria’s name, and so Cunard dutifully approached the reigning sovereign King George V with this formal request. According to the story they posed the request as permission to name the vessel after “England’s greatest queen” and King George – on a misunderstanding? - responded that his wife and consort, Queen Mary, “would be delighted” to have the ship named after her. Cunard Line was then bound to name the ship the Queen Mary, and thus it was.

The story comes to mind because it is on

the Queen Mary, now preserved and docked as a maritime museum, that we find the masterpieces

of the very fine but much neglected English artist and illustrator Kenneth Denton Shoesmith. An appreciation of his work is today largely confined to the small band of connoisseurs of maritime art, but it is deserving of a much wider audience, and for the present purposes, in keeping with the preoccupations of these pages, it deserves to be appreciated for its many orientalist and religious themes. Mr Shoesmith was destined to go to sea from an early age. While still a teenager he enlisted to be trained as a merchant marine at the Conway College; he was a so-called 'Conway Cadet' who graduated from the college then located on the HMS Conway docked in Liverpool which served as a training institute for British merchant sailors. At the same time, however, he found a passion for painting and eventually this talent led him to become a full-time artist. Here is his early painting of the Conway:

As readers can see, it is very competent work for such a young man - he was entirely self-taught other than completing a brief correspondence course - but conventional, realistic and unremarkable in style. As he continued painting, though, and found employment producing poster illustrations for maritime companies, his style matured and he adopted the methods and manners of the so-called 'Symbolist' and Art Deco schools in vogue prior to the Second War. In this mature style he produced many truly worthy works, many featuring exotic lands, before he died at the age of forty-eight in 1939. His master work followed a commission by the Cunard Line to produce murals for the new Queen Mary.

Here is another early work in his more realist style:

And another, this being a somewhat more impressionist watercolour rendering of the P & O steamer Strathmore:

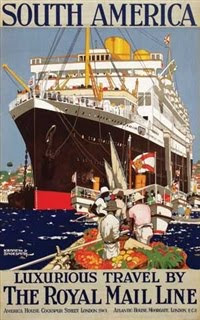

During the Edwardian age, of course, steamers of many great ocean lines - P & O (Pacific & Orient), Royal Mail, Blue Funnel, Cunard-White Star, Canadian Pacific and others - connected the many corners of the British Empire and east with west. As both a sailor and an artist Mr Shoesmith had the opportunity to travel the seven seas and never tired to sketching and painting both the ships that he loved and the distant lands to which they journeyed. His art is one of the most complete and lovely records of that regrettably by-gone age. As already mentioned, he made his living in the main producing images for travel posters such as the following:

Aside from, or incidental to, this commercial work he also produced paintings and illustrations for his own enjoyment. There are, for instance, such exceptional images as these of Egypt, North Africa and the Near East:

The most memorable images tend to be nocturnes; ships in exotic harbours at night seem to have been his forte. At best his style is as luminous, his colours as deep and as compelling, his subject as evocative as the work of his better known contemporary Nicholas Roerich. Three examples of Mr Shoesmith's nocturnes:

Also outstanding are the paintings he made of ships travelling the arctic passage, images of the midnight sun:

In the years 1934-36 he worked on murals for the Queen Mary. In these works we see him at the height of his powers. He produced a series of octagonal designs with literary themes and, for the first time, he turned to religious subject matter. Among the requirements for the Queen Mary were special installations for Catholic altars, altarpieces and reredos, provisions for the pious traveller. Mass was celebrated in the first class drawing room. He painted several images of the Virgin Mary for this location, as well as a screen that covered the altar when not in use. These are now regarded as his finest works. His most famous painting is that dubbed the 'Madonna of the Atlantic'. Here is a photograph of the artist working on it:

The prudish Cunard officials, however, took exception to the Christ child unclad (Good God! You can see His divine penis!) and demanded that Mr Shoesmith paint a drape over His nakedness. Thus the finished work appears as follows:

The folded panel covering the altar is a mediterranean sailing scene:

The work known as the 'Flower Market' in the first class cabin was a favourite of Winston Churchill. Below, the painting and a photograph of Mr Churchill giving a press conference in front of it:

The folded panel covering the altar is a mediterranean sailing scene:

The work known as the 'Flower Market' in the first class cabin was a favourite of Winston Churchill. Below, the painting and a photograph of Mr Churchill giving a press conference in front of it:

The stand out work among the Queen Mary murals, however, is surely another Madonna, the so-called Madonna of the Tall Ships. It is the same Madonna as the Madonna of the Atlantic, this time giving a benediction, and the Christ Child is suitably attired, but in the background is an array of tall sailing ships - in the foreground (rich in symbolism) three anchors and a lantern:

* * *

Yours,

Harper