The Khoo Kongsi - the largest ancestral shrine in George Town and one of the largest outside of China.

Among the Confucian virtues none is so important as filial piety, a religious sense of duty and loyalty to one’s family. It is conspicuous that exactly this virtue has declined in the modern West under the corrosive influence of liberalism where the “individual” – the rogue – is glorified and “freedom” – selfishness – comes before duty. Indeed, filial piety is one of the main things that separate societies that still retain a sense of tradition from those that have fallen into anarchic modernity. It has been very noticeable to this present author throughout his travels, first through India and Hindoostan, and now more recently through the Sino-Asiatic world. To the Indians, and to the Chinese, family is first. In Benares, for example, the author encountered a young man whose mother had become ill; he had to abandon his university studies to assist with the family business. He did so without hesitation and with no complaint. He knew that his first duty was not to pursue his own dream but to help the family, no question. Such a strong sense of family has almost disappeared from the modern West. In India, and among the Chinese, and among the Malays, the Japanese, and others too, even where modernity is fully embraced the traditional hold of family is not so eroded as it is in the West. These peoples pursue a modernity without anarchic liberalism, different models of modernity than that which has ravaged social cohesion in the West.

The centrality of family is especially underlined to the present author during his current sojourn in the old Chinese enclave of George Town, for George Town is the home to numerous clan associations or Kongsi. Upon arriving in George Town the taxi driver related that the great majority of tourists to the town nowadays are from southern China. They come here to visit the Kongsi of their ancestors. Clan, which is to say extended family grouped under one surname, remains an important feature of traditional social cohesion for the southern Chinese, even after several generations of state communist rule. In fact, there is now a strong movement among the southern Chinese to “search for roots” in order to repair the damage down by the Cultural Revolution. They travel to places such as George Town – Chinese settlements that avoided the Cultural Revolution and where traditional family organizations were strong - in order to renew their links with their past. It is called the Xungen movement - the movement to repair family lineages. There is a strong religious element involved. Family progenitors are revered and accorded sacred status. A Kongsi is not only a clan association but a religious organization. Families have their own preferred deities, along with so-called 'ancestor worship'. The Kongsi clan house acts not only as a meeting place for clan members but, most importantly, as a temple and as a place of worship.

George Town features numerous outstanding and illustrious traditional Kongsi. The Chinese clans have played an important role in the history of the city. There was a time when then tended to operate as secret societies, underworld fraternities, and there were several episodes of clan warfare. The British, very wisely, outlawed secret societies in the mid XIXth century and helped the clans become open, cooperative societies that made a positive contribution to the social good. In this, the clans operated as social welfare agencies, loci for trades, places of education, employment agencies, immigration offices and often as adjuncts to the judiciary and law enforcement. Clans acted to keep their members within the law and to settle disputes. On the whole, their contribution to George Town society was and continues to be extremely productive.

In organizational terms, a Kongsi is like a cooperative or a corporation. The extended family is ruled by the elder males - the bearers of the surname (a clan is patrilineal)- and they hold property in common. They invest in worthy projects and they distribute dividends to clan members. At times of economic downturn or fraying political life members can fall back upon the clan for common support. It is, in effect, what we might call a “distributist” system that combines the best features of a de-centralised capitalism with non-state collectivism, based at every point upon blood ties and the enduring reality of family. It is an impressive and time-honoured model of social organization and remains one of the foundations of traditional Chinese life.

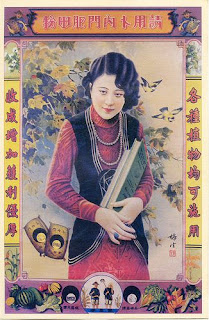

The pictures on this page illustrate aspects of some of the major Kongsi found in George Town.

THE CLAN ELDERS

A clan is patrilineal and its organisation patriarchal. Clans are organised under surnames. In the photograph above we see the current elders of the Khoo Kongsi in George Town (with the gentlemen dressed in traditional Changshan rather than Western business suites.)

ANCESTRAL ALTAR

In each Kongsi there is an ancestral altar. The names of ancestors are recorded on bamboo slips which are displayed on the altar. Worshippers pray to and revere the ancestors with the main devotional device being the lighting and offering of joss (incense).

In this picture, ancestors are recorded on tokens arranged in large conical pillars.

THE CLAN GODS

As well as the altar to the ancestors there is usually a main altar devoted to the preferred deity or deities of the clan. The deities are usually from so-called 'Chinese folk religion' (Confucianism), from Taoism or from Boodhism. Worship is syncretic.

THE ZUPU

The Zupu - the genealogical book. Each clan keeps detailed geneological records in a tome called a Zupu. Tracing and recording the lineage of the clan is an important duty of the Kongsi.

DISPLAYS OF ANCESTORS

Within each Kongsi there is usually a visual or a written display of deceased members of the clan. In some cases there are very extensive displays where visitoprs can come and search for photographs of their direct ancestors.

The ancestral hall of the Kongsi will often include memorabilia where the clan boasts of the achievements of its members. Higher education and positions of political power are especially noted.

VIEWS OF KONGSI

The Kongsi clan houses of George Town are beautiful examples of traditional Chinese architecture. Many of them are masterpieces of Chinese aesthetics.

As well as places of worship, the Kongsi are also places of recreation, with kitchens and meeting halls (and in the past - up until the Second World War - opium dens.)

THE CLAN JETTIES

In George Town several clans have settled along the waterfront, constructing their own jetties. There now remains numerous 'clan jetties' where members of the clan live in housing constructed on the jetties themselves. Much of their income now comes from tourism, but in the past it came from sea-trade and fishing.

* * *

Yours,

Harper McAlpine Black