By a strange turn of events the present writer finds himself ideally situated to complete a half-written and long-intended post to these pages on the matter of making visual depictions of the hobbit tales of J.R.R. Tolkien. The impetus for the post first arose out of a sense of overwhelming disgust at the appalling misrepresentations offered by that feeble film-maker Peter Jackson. The wide popularity of the movies speaks for itself: it was only a matter of time before Hollywood debased Tolkien into a form the post-literate plebian masses could digest. The Tolkien epics are approachable and modern in themselves, but they are replete with values and sensibilities now long gone from popular culture. They already belong to a former age. Jackson remedied this and dumbed them down for twenty-first century audiences.

This is not the place, though, for a full critique of Jackson's degeneracy. Suffice to say that he stripped the epics of any real sense of history, epic grandeur and mystical philology (which is the very fabric of the books), he took absurd and artless liberties with the motivations of the characters and the flow of the narrative, he filled the overblown cinema extravaganza with crude egotistic 'Oscar' baiting moments, and most obvious of all he depicted the hobbit hero Frodo as a dreary, snivelling sook. Indeed, it was as if there were only two settings in the movies: (1) Frodo and Sam are blubbering together and (2) Sam blubbers while Frodo is dying. Oh dear. This cheap melodrama went on and on and on. One critic caught the tone of such sentimentality with the astute observation: Jackson, he said, had turned Frodo and Sam into the guys from Brokeback Mountain. Indeed.

Frodo, grizzling yet again. The director clearly does not understand that copious displays of sooking is no substitute for the proper mythopoeic depiction of a conflicted heroic character.

And, as a disgruntled movie-goer asked: Has the entire Elven race suffered from a bout of mumps? And what about the immortal dialogue: "Looks like meat is back on the menu, boys!" Then there were the truly abysmal, cliched, ill-crafted slow-motion scenes - dozens of them. Pure Hollywood cheese. And this is to say nothing of the use of pseudo-folk music by Enya - yes, Enya! - whilst entirely ignoring the great musical treasury of song Tolkien himself had written. The movies were simply dreadful. There can be no doubt whatsoever that poor Professor Tolkien is turning in his grave.

To put this billion dollar travesty into context though, we must admit that, more generally, visual depictions of the Tolkien ouevre have a most ignoble history. There have been some very bad attempts to render these literary masterpieces into visual media. Tolkien himself resisted any such enterprise, and with good reason. He understood the very nature of 'fairy tale' and accordingly had a deep mistrust of the visual image. This is revealed in a famous (but overlooked) lecture in 1939:

In human art fantasy is best left to words, to true literature. In painting, for instance, the visual presentation of the fantastic image is technically too easy; the hand tends to outrun the mind, even to overthrow it...

We might take this as a general criticism of the entire genre of fantasy art. He also applied it to the question of illustration. He said very plainly:

However good in themselves, illustrations do little good to fairy-stories...

Why? He gave the following reason:

The radical distinction between all art (including drama) that offers a visible presentation and true literature is that it imposes one visible form. Literature works from mind to mind and is thus more progenitive. It is at once more universal and more poignantly particular.

And further, a point of which a second-rate Oscar-baiting hack like Peter Jackson has no comprehension:

Drama is naturally hostile to fantasy. ... Fantastic forms are not to be counterfeited.

Moreover, Tolkien made no exception for his own work, and was emphatic about the question of whether or not his own tales required visual supports and illustrations. In a letter to his publishers in 1967 he wrote:

I myself am not at all anxious for The Lord of the Rings to be illustrated by anybody whether a genius or not.

We can be sure, therefore, that he would have been horrified by the movies and their imposition of "one visual form." Who now can read The Fellowship of the Ring without Jackson's snivelling tear-jerking depiction of Frodo Baggins intruding upon the mind's eye? Once you have seen the movies there is a very real sense in which the books are ruined. To a lesser degree all illustrations present the same danger. It is a danger writers understand very well, artists understand hardly at all, and film-makers to no degree whatsoever.

* * *

The publishing history of the Tolkien hobbit works is littered with travesties, despite Professor Tolkien's best efforts to prevent it. We are reminded that writers are often at the mercy of half-witted publishers and their stable of talentless drawers. Suffice to consider a few examples of the cover art that has blighted The Hobbit over the years:

We could extend this gallery of bad covers much further, but this is enough for readers to see the dimensions of the problem. On some occasions publishers even went to great expense and employed renowned artists to supply cover art and some illustrations of the text, but very rarely with happy results. The letters of Professor Tolkien himself provide a record of his disdain for such efforts. The fantasy genre is, of course, a prosperous one in modern art and the works of Tolkien offer a compelling enticement for fantasy artists. Tolkien was inundated with letters from artists of various ilk hoping to provide illustrations for his texts. He was underwhelmed even by the best of them. Instead, he sometimes produced illustrations of his own, and wise publishers have appreciated their merits. Indeed, as we can see below, J.R.R. Tolkien was - quite apart from a great writer - a considerable artist in his own right, with a beautiful hand and a sure sense of line. In particular, his great sensitivity to language extended to a sensitivity for the calligraphic arts, and this has been featured somewhat in the more tasteful editions of his works. To this day the best editions of Tolkien feature his own drawings and experiments in runic scripts.

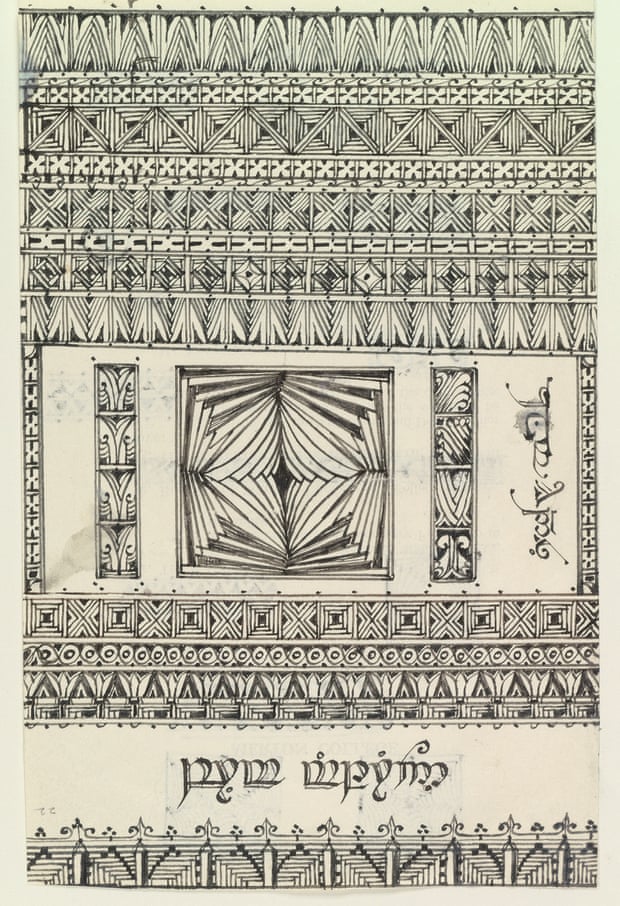

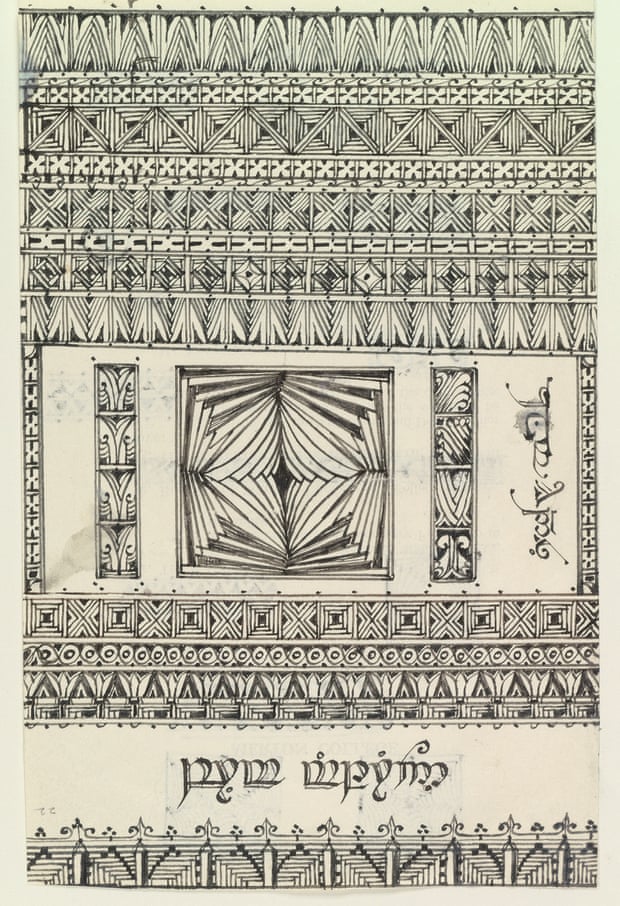

Here are two little-known samples of Tolkien's visual skills that underline his great ability:

A design Tolkien doodled on the back of an agenda notice

for a staff meeting at Merton College Oxford, 1957.

It features Elvish script.

A Japanese bamboo design by Tolkien showing

his great facility with ink pen drawing.

The few illustrations he made of scenes and places in the Middle Earth world are better known and have been published in calendars, posters and other forms, including book covers and feature pages in various editions of the hobbit tale books. There is no need to present them all here. A few will suffice to once again demonstrate his skill. His pictures have sometimes met with detractors amongst more formal artists who criticise them in various terms as "unpolished" or "untrained" or "a bit rough" or the like. These are the voices of those who have been clambering to have their own work illustrating his books - a very lucrative commission it would be. The present writer is firm in his view that, in fact, Tolkien's somewhat quaint drawings, pencil designs and watercolours capture the spirit of the text exactly.

* * *

THE CASE OF MARY FAIRBURN

THE CASE OF MARY FAIRBURN

There was only one artist who almost persuaded Tolkien to provide illustrations for his books. As it happens, the present writer was recently enjoying her hospitality whilst residing temporarily in her house in Castlemaine, Victoria. She is an English-born Australian artist named Mary Fairburn, now a spritely eighty-five years old. She sent some of her drawings to Professor Tolkien in 1967. Ordinarily, when he received such submissions he was polite but dismissive. In the case of Mary Fairburn's work he was unusually enthusiastic. His letters to her have survived. Here is the first of them, typewritten:

As readers will note, he describes her work as "splendid" and says "They are better pictures in themselves and also show far more attention to the text than any that have yet been submitted to me.” More importantly, her pictures, he says, were of such force that they might persuade him to change his views regarding an illustrated edition of his books. “After seeing your specimens," he says, "I am beginning to... think that an illustrated edition might be a good thing.” He draws her attention to his lecture on fairy tales (mentioned above) but, significantly, suggests that he might make an exception in her case.

This, however, did not come to pass. Professor Tolkien died and events at his publishers, Allen & Unwin, were ill-fated for Miss Fairburn. Subsequently, her work has never adorned any editions of the book, though some of her pictures have found their way into Tolkien calendars, such as the following:

And here below are a few of the illustrations that Professor Tolkien thought so worthy:

Readers will surely note a certain common spirit between her illustrations and Professor Tolkien's own drawings. Clearly, Miss Fairburn was able to enter into the author's imagination and capture its essence. Tolkien's enthusiasm was not misplaced. Over the years some have suggested that Tolkien was merely being polite and compassionate to the young artist - at the time Miss Fairburn was homeless and penniless and in some of his letters Tolkien expresses sympathy for her plight - but the quality of the Fairburn illustrations speaks against this. Tolkien's judgment was correct. Had she been given the chance, Mary Fairburn - more than any other artist then or since - would have been able to provide appropriate and apposite visual collaboration to the Tolkien texts.

Here is a copy of a further extant letter in Tolkien's unmistakable hand:

Outside of these letters it is now difficult to establish exactly what transpired in this case, and why Miss Fairburn met such firm rejection by Tolkien's publishers after his death. And worst, some of the illustrations Tolkien saw are now lost. The hapless Miss Fairburn set out on twenty or more years of wanderings, eventually settling in southern Australia, and was never able to keep a proper account of the work she left behind as she traveled. These days her encounters with Professor Tolkien are only a dim memory, and most of the surviving works that she made for him are in the hands of others on the far side of the world. Her career and her life would no doubt have been markedly different if matters had turned out otherwise, and so too would have been the history of visual representations of the Tolkien classics. One can only wish that the two of them - Tolkien and Fairburn - had found the opportunity for a full and fruitful collaboration.

Yours, Harper McAlpine Black

Dear Harper,

ReplyDeleteAlthough I agree wholeheartedly with yours and Tolkien's sentiments relating to Mary Fairburn's artworks, I think the early 1970s attempts were first time his works made their way in that direction and far worse than Jackson's, where their obvious grab for an undeserving sequel saw them ending the story well short of it's written conclusion.

As somebody who grew up with Tolkien's works, at least from the 1960s and who spent a lifetime spotting settings for a movie, I think Jackson did fairly well and honoured Tolkien's works better than might be expected given the circumstances and his stance regarding making all three movies or none at all, admirable.

Graham Dodsworth

graham@dodsworth.com.au