Love Lane in central George Town is so called, they say, because in former times it was the district in which Chinese businessmen were inclined to keep their mistresses. Today it is a fashionable street of terraced ‘link’ houses full of boutiques, tea houses and coffee shops, many with a nostalgic theme invoking the romance of this former era. The present author is staying in a cheap hotel just around the corner and not far from the Sunrise Sweetheart Café, a venue famous for ladies of easy virtue. It is in many of these shops and cafes on Love Lane - such as the very commodious number 41, the entrance of which is pictured below - that one can find reproductions of posters, advertisements and calendars from the golden era of Shanghai fashion, the 1920s and 30s – Chinese nostalgia. This ‘Out of Phase’ post is accordingly dedicated to the same. George Town is not all Chinese temples.

It was the fashion designers of Shanghai who transformed female attire and the Chinese female image under the Chinese nationalist Republic during the 1920s and 30s. After the turmoil of the revolution in the 1940s these same designers shifted to Hong Kong and Singapore and other outposts of Chinese culture, such as George Town, but by then the transformation they started had been complete. The attire of the Chinese woman had been changed forever. Chinese women were brought into modernity. The communists tended to regard the new fashions as ‘Western imperialism’ and, ironically, female attire after the revolution reverted to older, utilitarian, and hence more conservative styles. This regression into dowdiness reached its peak during the catastrophic Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s. In more recent times, the increasingly open policies of the People's Republic have re-embraced the fashion revolution of the early XXth century, which is to say they have rediscovered style and good taste and the great sartorial revolution of the 1920s and 30s is at last widely acknowledged in mainland China.

Here is a picture of traditional women's attire - the forerunner to the modern cheongsam - from the period immediately before the Shanghai design houses reinvented the garment in its modern form:

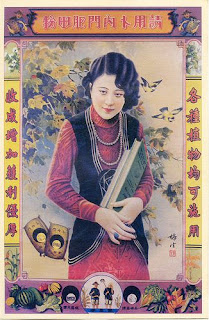

The liberation of the female form from the dowdy sacks of past styles was then embraced and celebrated in Chinese popular culture. Women in the cheongsam began to appear in advertising and in items of popular visual culture such as wall calendars. Some examples:

There are many modernities. In some cases it is a mode imposed by European civilization upon others. The Chinese, like the Japanese, were never going to be content to receive modernity passively like that. After resisting modernity for a long while, when they finally opened their societies to the new modern world they were determined to do so in their own way, with their own aesthetic values. They were never going to be mere imitators. They were going to appropriate and transform. Insofar as these images show a Westernized sensibility, it has been appropriated and transformed.

Yours,

Harper McAlpine Black

_by_Thomas_Jones_Barker.jpg)