DEMIURGIC POTENCY AND PLANETARY QUALITIES

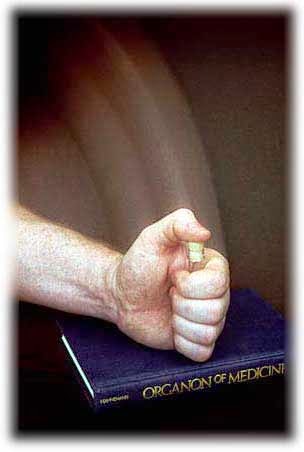

Succussion in Homoeopathy In contemporary biotherapeutic practice, the alchemical technique known as succussion is primarily associated with the potentization of homoeopathic medicines where the remedy is developed from the mother tincture up one of various mathematical scales. The founder of modern homoeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann, first attempted to treat his patients according to homoeopathic principles by raw tincture and then by simple dilution. At first, by his own account, he observed how quinine (as a tincture of cinchona bark) could both cause and cure the symptoms similar to malaria. Administering the pure tincture, however, would often cause adverse side effects in his patients, and so he began diluting the tincture by factors of one drop in ten (the X scale) or one drop in one hundred (the C scale) hoping for homoeopathic action (like curing like) without adverse reactions. Then, at some point in his early experiments – and probably drawing upon his extensive knowledge of ancient and medieval medical and alchemical techniques – he began succussing with each dilution. That is, taking one drop of tincture to ten or one hundred drops of a neutral medium, he would succuss the dilution by striking it forcibly and rhythmically against an elastic object such as a leather-bound book. This would constitute the first potency. Then he would take one drop of this, dilute it, and succuss, to make the second potency, and so forth. While simple dilution produced meager results and led to a diminishing of the homoeopathic effect until it ceased altogether, Hahnemann claimed that succussion preserved that effect and transmitted it through the chain of dilution. Succussion, he found, was crucial to the production of effective homoeopathic dilutions and provided the technique necessary to preserve the potency of the medicine while avoiding the side-effects of crude doses. When his critics jibed that homoeopathic dilution was like trying to cure the whole of Switzerland by adding a bucket of medicine to Lake Geneva, Hahnemann retorted that it might be so if only we could find some way to succuss Lake Geneva. Without succussion, the tincture is merely diluted. With succussion it is potentized and the homoeopathic action is preserved on the basis that the organism is super-sensitive to the similar remedy.

It hardly needs to be said that the physical basis of this defies conventional understandings of chemistry to this day, and thus is homoeopathy still subject to derision and claims that its medicines are merely placebos. Homoeopaths, moreover, have not been able to present any convincing account of what makes succussed homoeopathic dilutions effective. They must be content to say that it remains an empirical mystery, or they must hypothesize that, somehow, the medium used in dilution (water or alcohol) “remembers” information from one dilution to the next, that information being “imprinted” – somehow - by means of the succussion.

Of course, succussion is not limited to homoeopathy. It really just means striking a solution with force and this might be done in many pharmacological or alchemical operations, usually to loosen and dissolve active ingredients. Homoeopathy, though, has made special claims about the powers of succussion and its capacity to bring potency to dilutions. Hahnemann, we might say, discovered a more noble purpose for succussion than it just being a convenient mode of agitation. Outside of homeopathy, succussion is a method used in such operations as the production of tinctures, where, for example, the tincture will be succussed from time to time in order to assist the passage of active components from the plant matter to the menstruum. The tincture is thumped (succussed) to loosen active ingredients or, sometimes, to remove bubbles and air pockets. Homoeopathy elevates it to a loftier role beyond the merely mechanical and suggests that there is something more going on than just a loosening of physical parts. Homoeopathic practice suggests that succussion is not just a particular mode of agitation but has other, more significant, uses.

All the same, it should be noted that, strictly speaking, homoeopathy makes no claims about succussion in isolation; rather, in homoeopathy, succussion is always combined with dilution. Just as dilution alone does not work – as Hahnemann found – so too continuous succussion does not advance a homoeopathic preparation up the scale of potencies. There is no point in succussing a potency any more than necessary unless one also dilutes according to the scale being used. In homoeopathic pharmacy, that is, succussion and dilution go together and form a single process. The process is dilute/success/dilute/success, and so on. The succussion brings a kinetic element to the dilution without which the dilution would be merely a diminution of the medicine. Nevertheless, there seems to be some inherent vitality to succussion because, when a homoeopathic medicine has been sitting idle for a long while, homeopaths will often succuss it once more – without dilution – prior to its use. Succussion alone does not increase its potency in the formal sense, but the kinetic vitality imparted by succussion does seem essential to the life of homoeopathic medicines. They become flat – lose their “vibration” – without it. In alchemy succussion is not usually co-joined with dilution. It is just a method of agitating a preparation, and is used for much the same reasons as simple stirring.

Succussion Defined To be clear, though, let us note here – following careful distinctions made by Hahnemann himself - that succussion is not the same as merely tapping, jiggling, stirring, knocking, shaking or other means of agitation. It is a very particular, exact technique. To succuss a preparation means to hit it with some force upon a surface. Whatever the intent, to shake or stir is not quite the same thing. For homoeopathic purposes, certainly, Hahnemann found that a pronounced striking (technically called “succussion”) was necessary. The vial containing the preparation needs to be thumped upon an appropriately pliant surface (pliant, so that the vial does not break), and this needs to be done not just once but for a period of time in a rhythmic fashion. There is no agreement on the number of succussions required for each dilution – some say sixty, some say a hundred, some more, some less – but in every case the preparation is struck upon a surface with some force – thud-thud-thud-thud-thud-thud – in order to impart a series of kinetic shocks to the liquid contents. The kinetic nature of the process is evidently crucial because, again, merely shaking does not have the required effect. It is the specific practice of succussion – a rhythmic striking – that Hahnemann found to be efficacious.

Succussion in Alchemy The purpose of this short paper is to make some broader observations about succussion in the context of alchemy and to suggest a further use for succussion in contemporary alchemical practice. Prior to Hahnemann succussion was a humble process taken for granted and no one suspected that it had important applications or indeed any deep significance in a theoretical sense. Here we propose describing an important use for succussion and also making mention of its deeper meaning and background in alchemical symbolism. We are not concerned with the specific applications discovered by homoeopaths, because we are not concerned with the production of specifically homoeopathic pharmaceuticals. We have only discussed homeopathy because homoeopathy has made succussion its own. Here, instead, we are concerned with the spagyric arts more generally. In these arts succussion is a neglected technique. Taking a lead from homeopathy, our purpose is to realize its power as a method of “imprinting” qualities upon an alchemical preparation. In particular, this paper proposes a method whereby succussion is used to enhance the planetary or astrological qualities of alchemical preparations. Homoeopathy separates itself from alchemy in this regard, claims no astrological foundations, and insists that it is entirely empirical. It is a selective adaptation of alchemical methods to a particular, ancient theory of medicine. Alchemy always remains wedded to astrology; they are sister sciences that form a single Work. We want to suggest an important application of succussion in view of that, and then mention several theoretical and symbolic points that follow from it.

Planetary Qualities Alchemy is concerned with extracting, capturing and concentrating the sub-lunary manifestations of planetary forces, whether these are to be found embryonically in metals or in plants. In spagyric alchemy, plants are deemed to contain the planetary essences and the alchemical process consists of isolating those essences. Thus, for instance, certain herbs are valued because they are manifestations of certain planetary archetypes. Fennel is mercurial. The bay laurel is solar. And so on. Typically, herbs are harvested and processed on appropriate days and at appropriate hours according to established planetary correspondences. Herbs of Venus are harvested on Friday, the day ruled by that planet. Herbs of Saturn are harvested on Saturday, herbs of Mars on Tuesday And so on. This is familiar practice in contemporary plant alchemy, especially of the Paracelsian school, and there is no need to detail it here. There is a correspondence between plant and planet and the alchemical processes make use of these correspondences. Spagyric medicines, tinctures, elixirs and magestries are prepared with these correspondences in view and it is a key objective of all such alchemical operations that the product of the operation is imbued with concentrations of planetary forces. This is an essential feature of the theory and practice of alchemy since alchemy is concerned with the terrestrial manifestations of the celestial order.

Succussion can assist in this. The manner in which succussion “imprints” qualities to a medium can be used to extract, capture and concentrate planetary forces. It is a simple matter. In its most obvious application, the planetary qualities of a preparation may be enhanced by bringing succussion to it on the appropriate planetary days and/or at the appropriate planetary hours. Thus a solar preparation can be succussed each Sunday and, more particularly, during the hours of the Sun on Sunday. Let us suppose we are preparing a tincture of the bay laurel and in this we are seeking to enhance its solar properties. For a start, the plant material will be collected at the appropriate time, but after that it helps to attend to the tincture at similarly appropriate times. Many alchemists work like this in any case. They will strain the tincture at a time determined by the astrological correspondences, and wait for astrologically propitious times to conduct other operations upon the preparation. Some might even shake or stir the tincture at the appropriate times. This is all in order, but the point being made here is that succussion is a method naturally adapted to such processes. We should take note of Hahnemann’s experiments. Succussion – deliberate, prolonged rhythmic, kinetic striking – imparts a potency not found in stirring or shaking.

Sensitive Chaos There is not, as we have already said, any standing theory to satisfy conventional science of the action of succussion. Homoeopaths have turned to studies of sub-atomic molecular structures or to vibrational hypotheses to try to explain how succussion can “imprint” information onto a neutral medium. It is probably more useful to turn to studies such as Theodore Schwenk’s account of water systems in Sensitive Chaos for a meaningful theoretical framework. Schwenk’s model is based on a simple order/chaos dichotomy. Systems in chaos, he says, are sensitive to systems of order. Chaos is thus a window to creativity. Where there is chaos, a new order will impose itself. This might be what happens in succussion, either at sub-atomic or even more subtle levels. Each collision, each strike, shatters an existing order. A new order – a new code of information – then quickly gathers to fill that void. When the succussion is repeated over and over in rhythmic succession a particular order is “imprinted” upon the neutral medium.

Astrological Tides In any case, by these criteria succussion deserves a more prominent place in the alchemist’s repertoire of techniques, and if certain processes are timed according to astrological tides, and are deemed sensitive to planetary qualities, succussion is very likely to be more effective than some other processes such as shaking or stirring. It is somewhat by the way, but Schwenk’s study, dealing as it does with sensitive chaos in large natural systems, should lead us to consider the use of actual planetary formations in alchemical work rather than the traditional (and rather mechanical) calendar of tides. The imprints of succussion might be better adapted to actual cosmological events. This would suggest a way in which very specific cosmological qualities might be extracted, captured and concentrated. For example, the qualities of a certain celestial configuration, such as a trine relationship between, say, the Sun, Moon and Saturn, might be harnessed through these means. Every time that this same configuration occurred the preparation (tincture etc.) in question would be succussed. It would be struck upon a pliant surface sixty or so times. If it was succussed at these specific astrological junctures and at no others then, perforce, and by virtue of the sensitivity of the succussed medium, the qualities of that configuration would be “imprinted”.

This is a rather more organic approach than following a set calendar of planetary days and hours. For Mercurial preparations, for example, the alchemist chooses a particular astrological configuration in which Mercury is prominent - a Mercury/Solar conjunction, perhaps - and then succusses the preparation every time that configuration recurs. In practical terms, in fact, solar and lunar conjunctions lend themselves to this sort of approach, but less common configurations might be targeted as well, depending upon what qualities the alchemist seeks to deploy. All things considered, this might be a better approach than that which prevails in most Paracelsean practice today, namely just shaking preparations on a given day of the week. As it is, some alchemists will construct a chart of the heavens (horoscope) for some major operations. It might be better if, in general, alchemists were more cognizant of astrological cycles, just as it would certainly enhance the practice of astrology in modern times if astrologers were more aware of the connections of their art to alchemy. The “imprinting” for which we are supposing succussion to be an agent supposes an entirely hermetic mode of sensitivity. Alchemical preparations are routinely conceived to be microcosmic – it is therefore the macrocosm to which they will be sensitive. The hermetic maxim prevails in all such cases. We therefore take the microcosmic solution and succuss it in the deliberate Hahnemanian manner (though without serial dilution, because we are not making homoeopathic remedies) at carefully selected times, nodes of selected astrological potency. It is important not to succuss at other times. At other times – just like good wines - such preparations should be kept in a very stable state. Succussion occurs only when certain climates in the heavens return, and over time, by repetition, a certain condition of the cosmos is “imprinted” upon the menstruum. Again: shaking or stirring is to little avail. As Hahnemann found, there is something unique about succussion.

In order to produce potency, though, succussion must accompany dilution, or its equivalent. This insight of Hahnemann’s has its application in planetary alchemy in repeated operations at a series of identical astrological events. There is no merit in succussing a preparation for an extra long time once. Instead, it needs to be succussed at intervals, over and over, the more often the better. Each time the astrological configuration reoccurs, that is, the preparation is succussed sixty or so times. This is like one homoeopathic potency, 1x or 1c. The next time the same astrological configuration occurs the preparation is succussed again. This is then 2x or 2c. And so on. Hahnemann used a scale of dilutions. In the production of planetary spagyrics it is not a matter of dilution, but duration. The alchemist waits for the same aspect of cosmic order to return. The more often this is done, the greater the potency, the deeper the imprint. The x scale corresponds to astrological events of common regularity, while the c scale corresponds to events that occur with less regularity. In general terms, the x scale, we might say, is lunar, while the c scale is solar, or the x scale corresponds to the inferior planets and the c scale to the superior planets.

This is all by way of suggestion and follows from reflecting upon the powers of succussion exposed by homoeopathic pharmacy. It is entirely in order for alchemists to learn from the experience of their homoeopathic cousins. But it also follows from deeper reflections upon the nature of succussion as an alchemical method. Even though homoeopaths have made succussion (with dilution) their own, it is, we must insist here, a laboratory technique of a fundamentally alchemical nature. Certainly, Hahnemann did not invent it. It was already part of alchemical practice, but its roots had been forgotten and its powers unsuspected. So let us add some notes to put this practice back into a proper – that is, properly alchemical - perspective.

The Blacksmith’s Hammer We only come to realize its importance when we appreciate that, as a method of kinetic force, it is directly related to the arts of the primordial alchemist, the blacksmith. Too often do laboratory alchemists forget that the basis of their art is in metallurgy, that the laboratory is actually a glorified smithy and the alchemist is actually a glorified smith. Too readily do alchemists forget such roots, especially in these abstract times. But if a modern alchemist was to spend some time in a smithy beside the heat and sparks of a real forge, he would soon notice the importance of the blacksmith beating – in kinetic rhythm - his raw materials with his hammer, his most basic tool. There is a direct and very obvious connection between the blacksmith hammering at his anvil and the alchemist (or homoeopath) succussing his liquid preparations. Thud-thud-thud-thud.

If we were to explore this matter further we would add that the blacksmith, moreover, is, in this capacity (as in others), demiurgic, and alchemy is an essentially demiurgic art. Succussion then, is a demiurgic process and must therefore be related to earthquakes insofar as the blacksmith is the demiurgic Vulcan and practices, by mimesis, the volcanic formative arts. This is necessary background. To understand alchemy one should always remember that the retort of the laboratory is the crucible of the forge, and the crucible of the forge is the crater of the volcano. Such parallels are fundamental and ever-present. In alchemy, of course, processes of geological duration are compressed. Typically, the alchemist takes the embryonic metals from the womb of the earth, places them in his athanor, and brings them to quick maturity by imitating the processes that in nature will take aeons. The alchemist advances the demiurgic Work. That, finally, is what alchemy is all about. In this sense, succussion is like aeons of earthquakes compressed into a few minutes. In nature, each earthquake shatters the terrestrial order with terrible force but a new order, born of the heavens, asserts itself again. This, we should understand, is the large-scale, macrocosmic correlative to the laboratory process of succussion. This is the macrocosmic volcano-geological process that the alchemist is imitating.

Rumi and the Anvil This demiurgic symbolism is given beautiful expression in the story of the Muslim sage Rumi who, we are told, was one day walking through the bazaar when he heard the blacksmith’s hammer ringing out as it struck the anvil in steady rhythm. This innocent event was the catalyst for Rumi’s spiritual transformation. Suddenly, we are told, Rumi began whirling on the spot in ecstasy, his arms extended, in what is now the familiar and famous dance of his followers, the so-called whirling dervishes. By any account, the dance of the dervishes is planetary. Each dervish is an orb and they whirl around their own axis and about a central axis, the head dervish, the Sheihk. It is forgotten that it was the beat of the blacksmith’s hammer – demiurgic succussion - that caused Rumi’s transformation (like the transformation of metals) and that brought this celestial dance to earth. In this story the connection between succussion and the cosmological cycles of the planets is quite explicit.

Unseen to the observer of the dervish dance, furthermore, there is an internal alchemy with direct correlatives to the laboratory process of succussion. This is the so-called dhikr, or ‘prayer of remembrance’, which is the fundamental technique of Sufi spiritual transformation, and which has exact parallels in many other traditions. In dhikr, the dervish develops the practice of reciting the Divine Name internally, over and over, in serial repetition. The simplest form of it consists of reciting the Name of the Essence, Allah-Allah-Allah-Allah unceasingly, inwardly in the hidden chamber of the heart. The followers of Rumi do this as they conduct their planetary dance. The dhikr is described as ‘polishing the mirror of the heart’ or as ‘polishing a stone’ but in Sufi lore its origins are in the beat of the blacksmith’s hammer. It is the succussion of spiritual alchemy. What hammering is to the blacksmith’s art, so is succusion to the arts of the laboratory alchemist, and so too, in turn, is dhikr to the alchemy of the dervish.

Conclusion The alchemist would do well to reflect on this symbolism and therein know that there is much more to succussion than just a method of shaking a herbal preparation. Hahnemann, we realize, stumbled upon an alchemical secret. Succussion is a commonplace, basic method. Pounding a solution on a surface to “stir it up” - what could be more basic? Yet it is, as homoeopaths know, a key to great power. And when we consider it in a broader view of alchemy and the primitive roots of the Art and take into account the appropriate parallels we realize that its symbolic meaning takes us back to what is ultimately a demiurgic primordiality. The simple act of striking a vial on a leather-bound book has a cosmic meaning. In alchemy it is always true that there is deep significance to be found in even the simplest operations.

- R. Blackhirst