It is unfortunate therefore that the Argentine artist Xul Solar is usually counted as a surrealist and that the content of his work is mistaken for an exploration of the motifs of the unconscious. The prominence of Dali imposed a strong surrealist influence upon the Spanish-speaking world, no doubt, and Senor Solar would exhibit his work alongside others who fit more precisely in that category. But in fact he is not a surrealist painter in any proper sense. Stylistically, he is more akin to Kandinsky and Chagall - musicality and playfulness, respectively, are two of the strongest elements in his work - and what is mistaken for surrealist interests in his content is actually a deep and intelligent engagement with esotericism and the occult. The surrealists would sometimes exploit the esoteric and the occult but in this only achieved parody and pastiche. Xul Solar was an esoteric artist, a mystic (although technically speaking this is probably an incorrect label) and a student of the occult imagination in its more traditional sense. It is this that makes him interesting. He is not, like the surrealists proper, just a painter of nightmares.

His intellectual interests were extensive and he shared many of them with his close friend Jorg Luis Borges. Indeed, he appears in some of Senor Borges' stories and many of the same stories celebrate their shared interests. Largely, we might describe these interests as a fascination with esoteric systems, the most fundamental of such systems being language iteself. Solar was an inventor of imaginary languages. This is reflected in his visual work as well. He develops a visual language of marks and shapes and symbols and lines and colours (without any of the randomness and denial of system that characterizes surrealism.) Where it does not have ignoble motivations the intellectual principle of system is at the root of the occult. Solar was fascinated with language, games, number systems - much to his credit he was a dedicated duodecimalist - and by extension, qabbalah, tarot and above all astrology, the occult language par excellence. It has often been difficult for the art world to place him correctly: this is because these interests are outside of their usual purview. Fine artists are sometimes dabblers in the occult. Solar is more than that. He is not merely stealing a symbol here and there to impart a spurious aura of mystery: he is an occult artist in the fullest sense.

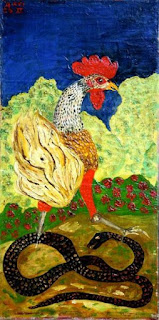

His tarot cards are quite charming and are surely one of the better creative renderings of the tarot made in the XXth century. Alongside the traditional symbolism of the arcana, which he renders with a child-like Chargallesque simplicity, he has added elements of his own symbolic developments, qabbalistic and astrological. Here are some samples:

The qabbalistic background to these images is found in his many explicitly qabbalistic drawings and paintings. In Western occultism, as it is normally presented in modern times at least, the Hebrew qabbalah represents a sort of matrix for the varied and sundry symbols of a wide range of esoteric systems. It is a sort of filing system, and of interest for both Solar and Borges for exactly that reason.

Note in these diagrams how the artist has made the qabbalistic system of ten (spheres) into a system of twelve planes - see the numbering on the sides and note that the numbers extend beyond 1 - 10. Solar was a duodecimalist - an advocate of a base 12 number system. Ordinarily, the qabbalah is a decimal system. Not for Xul Solar.

As it happens, the present author himself departs from the modern occultists on this point - he would prefer not to match the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet to the twenty-two trumps of the tarot purely because there are twenty-two of each, for example - but that is another matter. Senor Solar stays within that modern convention, and then uses it as the core structure of his art. In his time in Paris in the 1920s, Solar became acquainted with the mad mage Aleister Crowley and his foul-breathed mistress Leah Hirsig, and for a time they groomed him to become a member of their occult 'Orders'. The qabbalistic matrix is the core of Mr Crowley's system too. Sensibly, though, Solar headed back home to South America and apart from that brief encounter was not unduly influenced by the Crowley cult. Certainly, Borges made much better company and offered a far healthier occult intellectuality. We should be thankful for this. Crowley was a parasite who destroyed many fine minds and considerable talents - Victor Neuberg, for instance - and whether he knew it or not at the time Xul Solar saved both his soul and his art by side-stepping the self-styled 'Beast'.

The influence of Mr Crowley in the modern Western occult is so pervasive today that it is important to identify and celebrate those not under his sway. Xul Solar is one. Just as he is not properly classified as a "surrealist", neither, fortunately, is he an "occultist" in the Crowleyean sense. This is to say that just as he was not a painter of the dross of his own nightmares as were the surrealists, neither was he a cheap purveyor of the 'Dark Arts' like so many Crowley wanna-bes. His art has integrity, and his interest in esoteric systems - like that of Senor Borges - was genuine and elevated. His adopted name, Xul Solar - his real name being 'Oscar Agustín Alejandro Schulz Solari' - signals his benevolent disposition. Xul - a homonymn for 'Schulz' in Spanish - is L.U.X. backwards, the Latin for 'Light'. Xul Solar = the light of the Sun. There is nothing dark or menacing or sinister in the occult art of Xul Solar. He is not an explorer of an underworld. He is, rather, an explorer of the elevated imagination.

Not all of his work is quite to the present author's taste, but there is a sense of joy and wimpsy and a delight in imagined worlds that characterizes his best paintings, that makes him a modern favorite. There is music and mystery. And like Borges, the city-as-labyrinth - as opposed to the over-worked city-as-distopian-hell-hole - is one of his preferred themes.

And here, below, is the present author's rendering of Senor Solar's natal chart according to the methods the author prefers, notably the square chart and the insistence on the seven ancient planets. Without resorting to in-depth analysis, the notable feature of the chart is, surely, the conjunction of the two lights, Sun and Moon, in the midheaven. Solar , that is to say, was born towards noon at a New Moon. As we see in his chart, this configuration is culminating. In this sort of chart the so-called "angles" reveal all. In this case the native is indeed a 'New Moon' type, and we see at a glance why he went by the name of Xul Solar.

Yours,

Harper McAlpine Black